When you hear the word “mino”, you might picture Japanese folktales, traditional travelers, or even the fearsome Namahage wearing straw garments. The mino was a traditional raincoat woven from natural plants, and for centuries it was an essential part of everyday life in Japan.

Far more than just a piece of clothing, the mino reflects Japanese ingenuity, adaptation to the natural environment, and cultural identity. In this article, we’ll explore what a mino is, its features, history, and cultural significance.

What Is a “Mino”?

The mino sometimes appears in old movies, dramas, and even game. Today, let’s take a closer look at the mino!

Basic Role and Features of the Mino

The mino is a traditional Japanese raincoat made by weaving together rice straw, reeds, sedges, and other plants. Worn over clothing, it protected people from rain and snow. Interestingly, the shoulder area also acted as a cushion when carrying loads, making it highly practical.

Lightweight, durable, and waterproof, the mino was widely used in farming, fishing, forestry, and traveling. Its main weakness, however, was its high flammability, which meant people had to be careful near fires.

Materials and Regional Variations

While straw and reeds were most common, other materials included hemp bark, nettles, linden, wisteria, grape vines, and even seaweed in coastal regions.

Seaweed?!

I didn’t know that…

Each area developed its own type of mino depending on local resources, showcasing the close relationship between Japanese life and the natural environment.

Lightweight, Durable… but Weak Against Fire

The mino was prized for being easy to wear and providing excellent protection against rain. Its clever weaving technique allowed water to run off while keeping the wearer mobile. However, its greatest weakness was its vulnerability to fire—an ever-present risk in rural Japan.

The History of the Mino in Japan

Ancient Records in the Nihon Shoki

The earliest mention of the mino appears in the Nihon Shoki (Chronicles of Japan), one of Japan’s oldest historical texts. This shows that the mino has been in use since mythological times, making it one of Japan’s oldest traditional garments.

According to the Nihon Shoki, there’s a story where Deity Susanoo, after being banished from Takamagahara, wore a mino and kasa (straw raincoat and hat) and begged for shelter in the rain—but was refused.

That’s a sad tale. By the way, in Kanagawa Prefecture, there’s actually a shrine called Minokasa Shrine, dedicated to Susanoo.

If you are interested in Susanoo, please check the article below!

Popularization During the Edo Period

During the Sengoku period, it seems that even lower-ranking samurai used the mino as an effective raincoat.

By the Edo period (1603–1868), the mino had become widespread. Farmers, fishermen, travelers, and couriers all relied on it to endure the elements. Ukiyo-e woodblock prints frequently depicted people wearing mino, highlighting how common it was in daily life.

Continued Use Until the Showa Era

Even into the 1950s (Showa 30s), the mino was still used in farming and forestry. However, it eventually gave way to modern raincoats made of vinyl and nylon. Today, it is rarely used as functional clothing but continues to survive as a symbol of tradition in festivals and folklore.

Culture and the Mino

Essential for Farmers, Fishermen, and Travelers

For centuries, the mino was indispensable to everyday people—farmers working in fields, fishermen out at sea, and travelers journeying across Japan. It was truly the “commoner’s raincoat.”

Appearance in Folklore and Festivals

The mino also holds a place in Japanese folklore. One of the most famous examples is the Namahage of Akita Prefecture, a folkloric figure wearing a straw mino who visits households to warn lazy people. Many other yokai (Japanese spirits) and legendary figures are also depicted wearing mino, underscoring its cultural symbolism.

If you don’t know about Namahage, please read the article below as well.

The Role of the Mino in Modern Times

While no longer used as a daily raincoat, the mino continues to appear in festivals, folk rituals, and museum displays. As a symbol of traditional Japanese craftsmanship and harmony with nature, the mino is being rediscovered today for its cultural value.

I kind of want to try making a mino myself.

Maybe I could make one using the rice straw normally used for shimenawa (sacred ropes)?

Mino Q&A

- QWhat materials were used to make a mino?

- A

Common materials included rice straw, reeds, hemp bark, nettles, tree bark, and seaweed in coastal regions.

- QUntil when was the mino used in Japan?

- A

It was commonly used until the 1950s, after which modern raincoats replaced it.

- QCan you still see a mino today?

- A

Yes! They appear in festivals, museums and cultural heritage events.

Final Thoughts about Mino

The mino was not just clothing but a tool of survival, crafted from natural materials to protect people from rain and snow. Lightweight, durable, and waterproof, it supported the lives of farmers, fishermen, and travelers for thousands of years.

From its earliest mention in ancient chronicles to its widespread use in the Edo and Showa eras, the mino is a testament to Japanese ingenuity and adaptability. Today, while its practical use has declined, it remains alive in folklore, festivals, and cultural memory as a symbol of Japan’s traditional lifestyle.

The mino may no longer keep people dry on rainy days, but it continues to connect us with the spirit of Japan’s past.

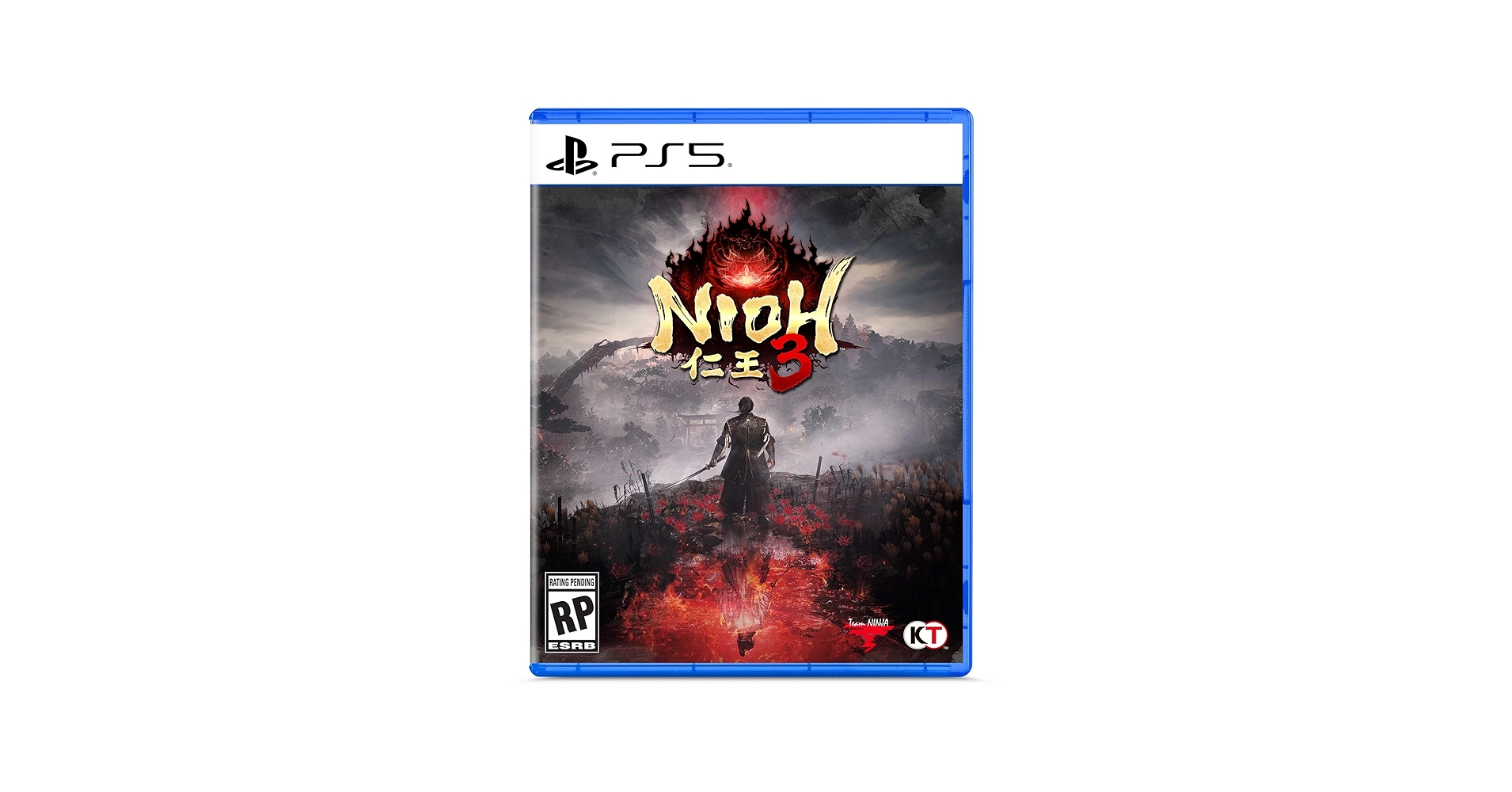

If you are interested in Japanese culture, and you love gaming, you may love these games! Let’s play!

Yes! Let’s play!

Comments