When you think of Japanese New Year, one food immediately comes to mind—mochi (rice cakes). Whether in ozoni (New Year’s soup), kinako mochi, or grilled with soy sauce, mochi is an essential part of Japanese celebrations.

But have you ever wondered how mochi is made? Traditionally, Japanese families and communities gather to perform mochitsuki, the art of pounding steamed rice into chewy, delicious mochi.

In this article, we’ll explore the origins of mochitsuki, the cultural significance of mochi, and fun customs like “mochi throwing” that might surprise you.

Today’s topic is mochitsuki! It’s that exciting year-end event that makes you feel like a kid again, even as an adult.

What Is Mochitsuki?

If you’ve never seen mochitsuki before, check out the video above first. It takes two people: one to pound the rice and another to turn it over. By the way, in real life it’s usually done at a much slower pace, haha.

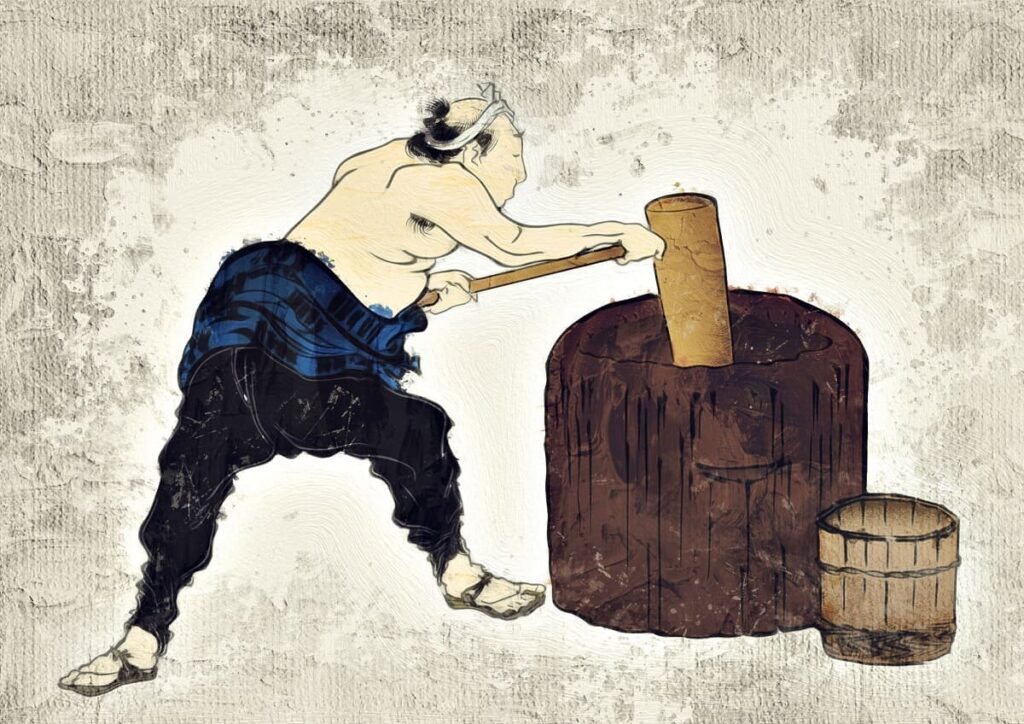

Mochitsuki is the traditional Japanese method of making mochi. Steamed glutinous rice is placed into a large mortar called an usu, and then pounded with a heavy wooden mallet known as a kine.

It’s usually done by two people working in rhythm: one pounds the rice, while the other folds and turns it between strikes. The teamwork, the chants of “Yoisho!”, and the festive atmosphere make mochitsuki not only about food, but also about bonding.

In the past, families made mochi at home every December to prepare for the New Year. Today, mochitsuki is more commonly seen at schools, shrines, and community events, where people can join in and taste freshly pounded mochi.

When I was a child, my grandparents held mochitsuki every year. I always looked forward to “helping out”—which really meant sneaking in some taste tests. These days, we use a mochi-making machine, which I’ll explain more about later in this article.

When Is Mochitsuki Held?

Traditionally, mochitsuki is performed at the end of December, especially on December 28, which is considered lucky because the number 8 represents prosperity.

In contrast, December 29 was avoided because it was nicknamed “ku-mochi,” meaning “suffering mochi.” Mochi made on December 31 was also considered inauspicious and called “overnight mochi,” symbolizing last-minute preparation.

That’s why most families aimed to finish their mochitsuki before the 28th to properly welcome the New Year.

Once mochitsuki is finished and the mochi is ready for storage, we place it in the coldest room in the house.

We don’t use any heating in that room, just to prevent mold from growing!

The History of Mochitsuki

Mochi is more than just food in Japan—it is deeply tied to spiritual beliefs. As far back as the Nara period (8th century), people were making mochi as offerings to the gods.

Apparently, mochi itself has existed since the Jomon period, but mochitsuki became popular much later.

In Shinto tradition, mochi is offered to the Toshigami-sama, the deity of the New Year, who blesses families with health and prosperity. Eating the mochi afterward was believed to bring good fortune for the coming year.

If you are interested in Toshigami-sama, please read the article below as well!

How Mochi Is Made (Step by Step)

Here’s a simplified look at the mochitsuki process:

Wash the glutinous rice | Soak it in water overnight. |

Steam the rice | Cook until soft and sticky. |

Place in the mortar (usu) | Start by kneading and pressing the rice. |

Pound the rice (mochitsuki) | One person pounds while another folds the rice. |

Shape the mochi | Form into round cakes or cut blocks, dusting with flour to prevent sticking. |

The person in charge of turning the rice during mochitsuki has a tough job. Since the rice is fresh out of the steamer, it’s incredibly hot!

Even just shaping freshly made mochi can burn your hands a little.

Freshly made mochi can be eaten plain, with kinako (soybean flour), sweet red bean paste, or wrapped in nori seaweed with soy sauce.

What Is Mochi Throwing?

Another fun tradition involving mochi is mochi-nage (“mochi throwing”). During festivals, weddings, or the framework stage of building a new house, families throw small mochi into the crowd.

Catching mochi is considered lucky, as it represents sharing blessings and happiness. In some regions, red and white mochi (colors of good fortune) are used.

In the area where I grew up, we had mochi-throwing festivals during celebrations. The scramble to grab mochi was so much fun!

Mochi in Japanese Culture

Mochi isn’t just for New Year—it appears in many seasonal celebrations:

- Kagami Mochi (decorative mochi for New Year)

- Hishi Mochi (diamond-shaped mochi for Girls’ Festival)

- Kashiwa Mochi (oak leaf mochi for Boys’ Festival)

- Mochi tossing at weddings and festivals

Throughout the year, mochi has been a symbol of celebration, good fortune, and family unity.

If you are interested in Kagamimochi,

check the article below!

Mochitsuki Today

Modern households often use electric mochi-making machines, which steam and knead rice automatically. These machines make it easy to enjoy fresh mochi at home.

However, nothing beats the excitement of traditional mochitsuki—hearing the rhythm of the pounding, joining with neighbors, and tasting mochi warm from the usu. Many towns and tourist spots now offer mochitsuki demonstrations, making it a must-try cultural experience for visitors to Japan.

Nowadays, even in my own family, we make mochi with a mochi machine. It’s so much easier compared to the days of pounding it all by hand!

Tools Used in Mochitsuki

Traditional mochitsuki requires some unique tools:

Usu (mortar) | A large stone or wooden bowl. |

Kine (mallet) | A wooden mallet used for pounding. |

Seiro (steamer) | Bamboo or wooden steamer for cooking rice. |

These tools are often handed down through generations, symbolizing continuity and tradition.

Final Thoughts about Mochitsuki

Mochi and mochitsuki are more than food—they are a window into Japanese tradition, spirituality, and community life. From welcoming the gods of the New Year to sharing blessings with neighbors, mochi has long symbolized togetherness and celebration.

If you ever get the chance to join a mochitsuki event in Japan, don’t miss it. Pound the rice, shout along with the crowd, and enjoy the chewy mochi you helped make—it’s the best way to experience Japanese culture firsthand.

If you are interested in Japanese culture, and you love gaming, you may love these games! Let’s play!

Yes! Let’s play!

Comments